“Dry Needling” – What it is and How does it work?

The term “dry needling” has become ever more popular in the past few years in the world of sports medicine, pain management and physical therapies in general. As clinicians we often find ourselves answering very similar questions regarding its use, how it works and its’ origins. With that in mind we have set about trying to answer the big ones in this article!

What Is Dry Needling?

Dry needling refers to the insertion of a solid filament needle that passes through the skin to provoke a physiological response which is most commonly to reduce the sensation of pain and provoke an optimal tissue state.

Why is it called DRY Needling?

During the development of this technique, the early doctors used local anaesthetic (lidocaine) to inject into sensitive areas of muscle. Their later observations were that this did not provide superior outcome to purely inserting a needle. More recently, two meta-analyses (large analyse of the research) have demonstrated that both wet needling (lidocaine injections) and TrP-DN seem to be similarly effective for neck/shoulder myofascial pain without clear differences between both needling therapies.

Trigger Point Dry Needling

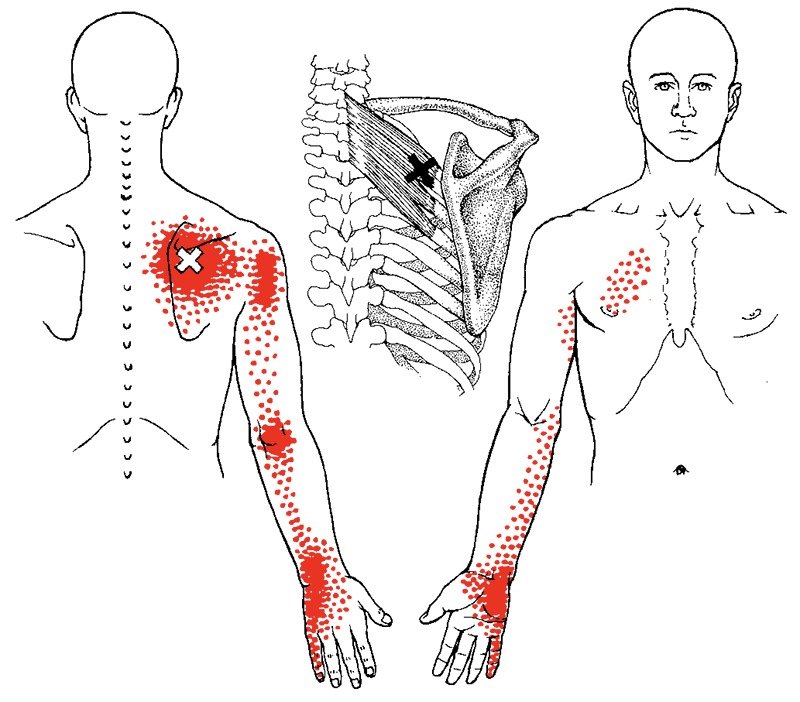

One of the more common types of dry needling is Trigger Point Dry Needling. This refers specifically to inserting the needle into “knots” in the tissue. These “knots” that you can often feel in your neck are referred to by clinicians as hyper-irritable bands of tissue. It is likely that these areas arise through a combination of factors that include overuse, underuse, trauma and underlying tissue injury. This causes a taut band that produces pain distributed in a familiar pattern often far from the site of the actual problem (see figure 1). These bands can not only cause “sensory” problems such as pain, but some authors have discussed them contributing to “motor” symptoms such as altered muscle activation patterns and higher tendency to fatigue.

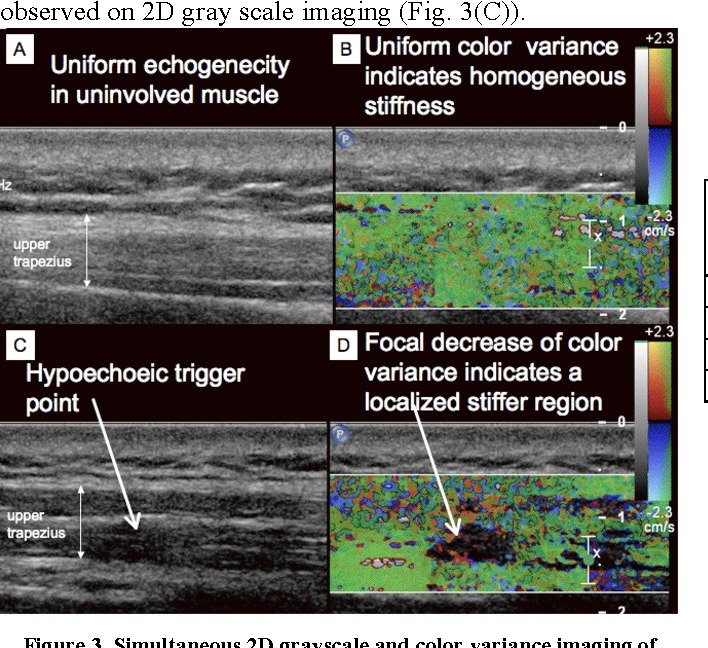

Amazingly, these “knots” can now be visualised with a research technology called ultrasound elastography (figure 2) and on imaging can be seen to be relieved with this technique. Research has also shown higher electrical activity in the region of trigger points using EMG.

Technology called ultrasound optimised with "vibration sonoelastography

The Technique Explained Further

Research in this area continues to develop but at present there are number of explanations for the relief commonly felt after dry needling.

1) De-activating Trigger Points

The needle once passed into this irritable tissue (or “knot”) first grasps around the needle, then relaxes, causing the once disorganised fibres to re-distribute and returning the tissue to its appropriate length and restoring local blood flow. This process is called a “local twitch response” and is the hallmark of a myofascial trigger point.

2) Restoring an optimal biochemical environment

The areas around a trigger point have been shown in the research to often have higher levels of pro-inflammatory mediators and substances that can provoke a painful sensation as well as reduced tissue oxygenation. Dry needling has been shown to help in restoring this environment.

3) Restoring normal electrophysiological activity at the connection of nerve to muscle

Dry needling has been shown (in rodent and rabbit studies) to normalise increased “motor end plate” activity in myofascial trigger points however it is worth noting that in recent human studies have failed to show significant difference when compared to a sham needling intervention. As with most techniques in medicine, more research is always needed!

4) Altering the nervous system – the spine and brain.

It has been found that trigger points themselves are capable not just of causing a local tissue “issue” but that they actually can sensitise the person at a spinal and brain level. By changing the local chemical environment (discussed above), less “danger” signals are sent to the spine which essentially calms the area and has actually been shown to change the chemical environment around the relevant spinal segment, explaining the often surprising effects of treating the left limb and reducing pain on the right side. Reduced irritation of the spinal segment then reduces danger signals being sent to the brain and thus areas of the brain related to processing of threats and production of pain start to calm too.

There are of course other theories and mechanisms and a skilled clinician may utilise different needling techniques such as twisting the needle (to stretch fascial tissues) and induce a strong “opioid” response, “pecking” the bone to provoke an element of microtrauma that results in a new healing response and connecting the needles with a small pulsed current to provoke the release of pain relieving neurotransmitters in the brain. Essentially needling is only as effective as the person using and utilising them, dosing and consistently considering risk versus benefit.

Is Dry Needling Different to Acupuncture?

From the outside it may look very similar and it is indeed likely that many of the therapeutic mechanisms that result in pain relief are similar. This author has trained in both. Acupuncture is based on a completely independent paradigm of Traditional Chinese Medicine that sets about aiming to create balance through optimal flow of Qi (energy) within the body. Needles are inserted according the assessment of this and restore balance. Dry needling variances are based upon a structural understanding of dysfunctional tissue, an orthopaedic assessment of the structures and palpation of hyperirritable injured tissue. Needle location is largely based upon an understanding of the anatomy and neurology of the patient we are trying to manage rather than altering “energy flow”. Though much wisdom and technique can be learnt from our Chinese colleagues, the origins of dry needling likely date back to the injection of these plotted irritable bands with lidocaine that were first discovered by Janet Travell a cardiologist the person physician of John F Kennedy.

Does dry needling hurt?

As with many therapeutic modalities there is often a short term discomfort and many patients find the initial feeling odd especially when the “twitch response” is encountered. My clinical experience however is that many patients also find it very satisfying to feel the point they have been struggling to access addressed directly and the weird feeling soon becomes a welcome experience.

Does dry needling cause bleeding or pain after the treatment?

As with any treatment that breaks the skin barrier there is always a small risk of side effects. The most commonly encountered is up to 36 hours post needling soreness which is often described as a bruise type sensation. Most patients feel sore for up to 24 hours but many report that the soreness actually settles in a few hours. Bleeding occasionally occurs (1 in 20 points) but this invariably stops with firm pressure in less than a minute. Other risks are documented such as infection and injury to other structures however in over a decade of daily practice, I have thankfully not yet encountered these.

Do you have to complete specialised training to practice dry needling?

Minimum standards for dry needling vary greatly internationally. Currently in Singapore, it is an area that is not well regulated and there are many with very little healthcare training such as movement and massage therapists that are practicing with only 16 hours of supervised training.

It is worth considering that even when Physiotherapists have the same 16 hours training that it is on the background of 4 years formal University based undergraduate training and often postgraduate masters and doctoral programmes based upon the anatomy, physiology, pathology and dysfunction of the neuromusculoskeletal system. The technique is therefore the extension of this.

At Integrative Physio, Matthew Winter has, in addition to a year’s worth of undergraduate training in Chinese Acupuncture for Pain, completed over 50 hours of further formal training, including with one of the founders of the technique, Dr Jan Dommerholt. In addition to this he has over a decade experience of daily clinical use.

References

Gattie, E., Cleland, J. A., & Snodgrass, S. (2017). The Effectiveness of Trigger Point Dry Needling for Musculoskeletal Conditions by Physical Therapists: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 47(3), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7096

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; (2016 Aug 22). Dry Needling and Injection for Musculoskeletal and Joint Disorders: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK395716/#_NBK395716_pubdet_

Bynum, R., Garcia, O., Herbst, E., Kossa, M., Liou, K., Cowan, A., & Hilton, C. (2021). Effects of Dry Needling on Spasticity and Range of Motion: A Systematic Review. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 75(1), 7501205030p1–7501205030p13. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.041798

David Legge; (May 2014) Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 22(3) DOI:10.3109/10582452.2014.883041

De Meulemeester, K. , Calders, P. & Cagnie, B. (2022). Exploring the Underlying Mechanisms of Action of Dry Needling. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 101 (1), 18-25. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001732.

Sikdar, S., Shah, J.P., Gilliams, E.A., Gebreab, T., & Gerber, L.H. (2008). Assessment of myofascial trigger points (MTrPs): A new application of ultrasound imaging and vibration sonoelastography. 2008 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 5585-5588.